How NSO Group Helps Countries Hack Targets

The controversial Israeli spyware company is more involved in hacking targets than previously believed, according to sources.

IMAGE: JACK GUEZ/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

A blockbuster lawsuit involving the most popular chat app in the world and the most infamous spyware company in the world has given us concrete details about how the secretive Israeli spy firm NSO Group helps countries hack journalists, activists, and other targets around the world.

WhatsApp, which is owned by Facebook, filed a lawsuit against NSO Group in a California court on Tuesday. NSO makes Pegasus, a surveillance product that hacks cellphones and is used by government agencies around the world to intercept and read data on the hacked devices. WhatsApp alleges that NSO was sending malware to take control of phones via WhatsApp and was using Facebook infrastructure as part of its hacking campaign.

Pegasus has been used by Saudi Arabia, Mexico, United Arab Emirates, and other countries with questionable and poor records on human rights to hack activists, dissidents, and journalists, according to internet watchdog Citizen Lab, which monitors spyware for the University of Toronto.

Few outside of the governments that use Pegasus have details about how the software actually works, but screenshots of the software and a contract included in the WhatsApp lawsuit have helped confirm some of Motherboard's own reporting about how Pegasus is implemented. In simple terms, NSO provides hacking as a streamlined service, which means a lot of the actual tech is in the company’s own control, and NSO can offer hands-on assistance to the government employees who use it. In public statements, NSO has tried to distance itself from the actual hacking.

“We have no way to know what they do it the system,” Omri Lavie, one of NSO’s co-founders, said on a podcast in 2017, according to a translation on an Israeli website. “I don’t want to know. I don’t want to be an intelligence partner.”

The contract and our reporting suggests that NSO is much more involved in hacking its targets than it has publicly said. NSO has maintained that it merely sells tools to governments and that it does not have specific knowledge of who its clients hack.

Do you work or used to work at NSO Group? We’d love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at lorenzofb@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzo@motherboard.tv. You can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, Wickr on josephcox, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

That's important, because WhatsApp accused the Israeli surveillance software maker of using WhatsApp’s servers to help its government customers around the world target more than 1,400 people in 20 countries, including more than “100 cases of abusive targeting of human rights defenders,” according Citizen Lab, who helped WhatsApp in its investigation. It's one thing to help a government spy on suspected terrorists and child abusers and another to help authoritarian governments target activists and dissidents critical of those governments, as the United Nations's Special Rapporteur on Free Expression David Kaye pointed out in a letter to NSO sent earlier this month, which noted there is a "legacy of harm" facilitated by NSO.

A source who works in the offensive cybersecurity industry and is familiar with NSO software said in an online chat that in at least some cases, NSO customers are given an interface to work with the company to use its tools.

“You get a big server installation. You get a website,” they said, referring to an interface where customers can input target information—such as a phone number—as well as see the target’s data after they get hacked.

NSO also helps some customers craft phishing messages that the target is more likely to click.

“Then engineers help you setup a believable message that sends to targets [sic] via your infrastructure,” the source added.

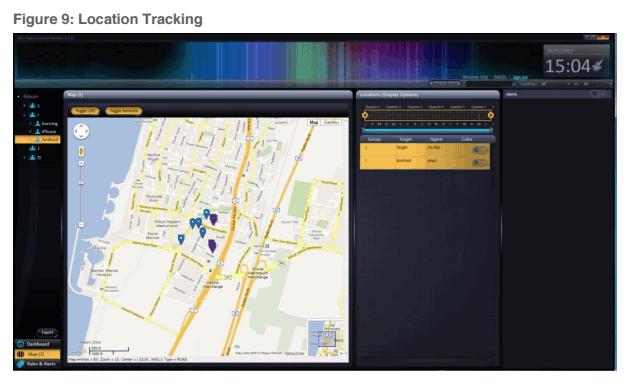

SCREENSHOTS OF NSO’S CUSTOMER INTERFACE, TAKEN FROM AN OLD LEAKED BROCHURE

NSO employees not only help customers set up the system, but troubleshoot it for them. Some NSO engineers, who are essentially IT support for customers, sit in the same room when operations are run, according to the source, who said they have seen NSO’s products in action, and who asked to remain anonymous to discuss sensitive topics. (A second source with direct knowledge of NSO’s operations confirmed that customers get a server, an interface. A third source confirmed some customers have NSO engineers on site.)

Most customers don’t have visibility into the tools used in the attack; they just type in a target phone number and NSO's system handles the rest.

This description of NSO's level of involvement is backed up by a contract included in the WhatsApp lawsuit. The level of support NSO gives customers depends on how much the customer pays.

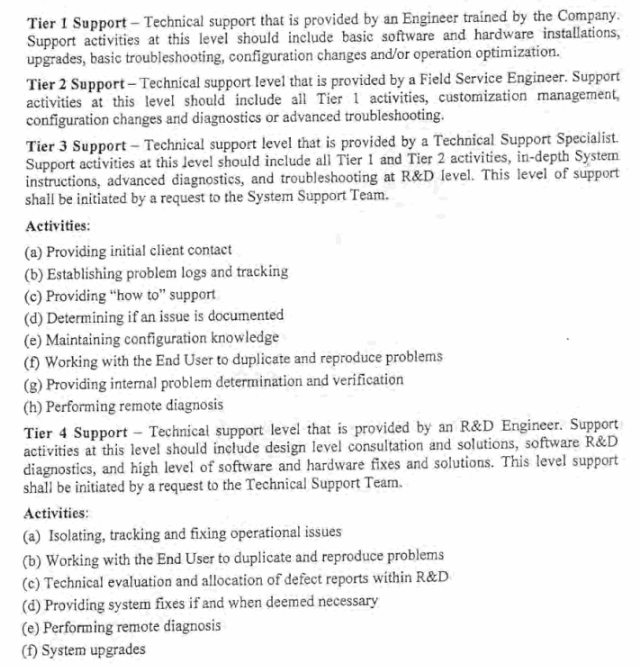

That 2015 contract, between the National Communication Authority of the Republic of Ghana, NSO, and a local reseller, shows the spyware company offering four levels of customer support for Pegasus. Ghana's purchase of NSO tools was previously reported by Ghana Business News.

NSO offers four tiers of support. At the lower end, NSO says it will provide basic software and hardware installations and troubleshooting. For Tier 4, the contract says NSO will offer technical support by an "R&D [research and development] Engineer," including "Isolating, tracking and fixing operational issues," and "Technical evaluation and allocation of defect reports within R&D."

"The Company will provide the End User with assistance in operating, managing and configuring the System as well as resolving any Software technical issues," another part of the contract reads. The "Support Period Consideration" costs 22 percent of the overall system price, which for Ghana was $8 million, according to the contract.

THE FOUR TIERS OF SUPPORT THAT NSO CUSTOMERS CAN CHOOSE FROM, ACCORDING TO A CONTRACT WITH THE GHANA GOVERNMENT.

The contract also details the specific hardware NSO provides to the client to operate the system itself. In the Ghana case, this laundry list includes Dell produced servers and Intel processors.

The NSO staff may not press the Enter key to actually hack the target, but they are involved in essentially every other step of the process, according to the sources.

Mexico, which has spent a reported $80 million on NSO software between 2011 and 2017, flew a phone to NSO’s offices so that the engineers could install spyware on it before the phone was delivered to the infamous drug cartel leader Joaquin “el Chapo” Guzman, according to Israeli publication Ynet News.

Pegasus customers, then, get a locked-down workstation that’s as easy to use as possible, since some customers don’t have the knowledge, skills, or time to learn the intricacies of hacking targets who use modern smartphones made by Google and Apple.

We asked NSO four specific yes or no questions. A company spokesperson responded with this statement: “Under no circumstances does NSO operate the systems that are licensed to our customers; to do so would violate many laws and regulations, as well as our own policies. NSO’s products are only provided to intelligence and law enforcement agencies after a strict licensing and vetting process, and after training the clients use the system on their own for preventing and investigating terror and serious crime.”

”NSO does not operate its technology itself,” the company said. ”In the event of potential or suspected misuse, the company retains the contractual right to investigate the products’ use and would be able to identify the phone numbers used, with the cooperation of the end user. This would only occur under the context of an investigation.”

Saudi Arabia, which has been reported to be an NSO customer, came under fire last year for killing former Washington Post reporter Jamal Khashoggi. After Khashoggi’s death, news reports revealed that his close circle of friends was targeted with NSO spyware.

After public pressure mounted on the company, NSO said that its software wasn’t used against Khashoggi. It is unclear how NSO can simultaneously say it does not know who its clients target while stating its software was not used against a specific person.

“It is possible that some companies are making genuine attempts to address the charges of complicity in surveillance-based repression and abuses,” Kaye wrote in his letter to NSO. “There are, however, virtually no public disclosure and accountability processes to verify such claims.”

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten

Opmerking: Alleen leden van deze blog kunnen een reactie posten.