The 1977 White House climate memo that should have changed the world

I

Years before the climate crisis was part of national discourse, this memo outlined what was known – and feared – about the crisis at the time. It was prescient in many ways. Did anyone listen?

By July 1977, President Jimmy Carter had only been in office for seven months, but he had already built a reputation for being focused on environmental issues. For one, by installing solar panels on the White House. He had also announced a national renewable energy plan .

“We must start now to develop the new, unconventional sources of energy we will rely on in the next century,” he said in an address to the nation outlining its main goals.

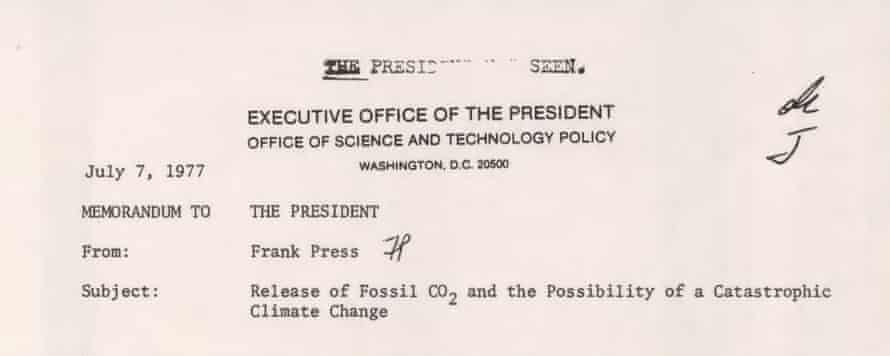

The climate memo arrived on his desk a few days after the Independence Day celebrations on July 4. It has the ominous title “Release of Fossil CO2 and the Possibility of a Catastrophic Climate Change.”

One of the first thing that stands out is the stamp at the top, partially elided, saying THE PRESIDENT HAS SEEN.

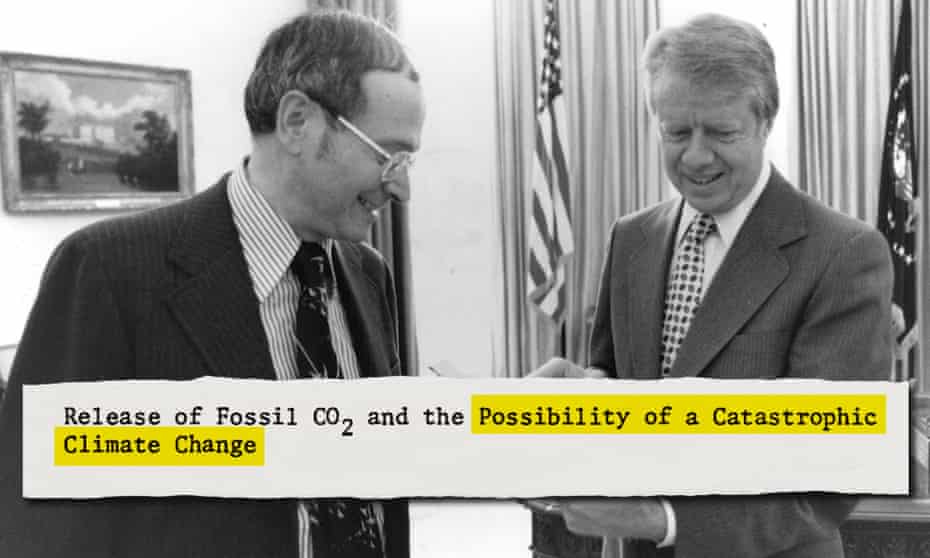

The memo’s author was Frank Press, Carter’s chief science adviser and director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy. Press was a tall, serious, geophysicist who had grown up poor in a Jewish family in Brooklyn, and was described as “brilliant” by his colleagues. Before working with the Carter administration, he had been director of the Seismological Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, and had consulted for federal agencies including the Navy and NASA.

“Carter had a great respect for Frank [Press] and for science,” said Stu Eizenstat, who served as Carter’s chief domestic policy adviser from 1977 to 1981.

Press starts the memo by laying out the science of the climate crisis as it was understood at the time.

Fossil fuel combustion has increased at an exponential rate over the last 100 years. As a result, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 is now 12 percent above the pre-industrial revolution level and may grow to 1.5 to 2.0 times that level within 60 years. Because of the “greenhouse effect” of atmospheric CO2 the increased concentration will induce a global climatic warming of anywhere from 0.5 to 5°C.

These far-sighted assertions were in line with the climate science that originated the previous decade, when the US government funded major science agencies focused on space, atmospheric and ocean science. Research produced for President Lyndon B Johnson in 1965 found that billions of tons of “carbon dioxide is being added to the earth’s atmosphere by the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas”.

Press’s memo was on the mark. In 2021, for the first time ever, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 reached 420PPM, the halfway point to the doubling of pre-industrial CO2 levels that Press posited.

The potential effect on the environment of a climatic fluctuation of such rapidity could be catastrophic and calls for an impact assessment of unprecedented importance and difficulty. A rapid climatic change may result in large scale crop failures at a time when an increased world population taxes agriculture to the limits of productivity.

Press was right. We have indeed seen the catastrophic effects of a climatic fluctuation, in the form of increasingly severe weather events including droughts, heatwaves, and hurricanes of greater intensity. Meanwhile, in many parts of the world heating has already stemmed increases in agricultural productivity, and large-scale food production crises are thought to be possible.

The urgency of the problem derives from our inability to shift rapidly to non-fossil fuel sources once the climatic effects become evident not long after the year 2000; the situation could grow out of control before alternate energy sources and other remedial actions become effective.

This is correct. By the 2000s, the effects of the climate crisis had become apparent in some regions in the form of more deadly heat waves and stronger floods and droughts.

Natural dissipation of C02 would not occur for a millennium after fossil fuel combustion was markedly reduced.

This prediction by Press was actually debunked at least a decade ago. Scientists used to believe that some warming was “baked in”, but scientists have since found that as soon as CO2 emissions stop rising, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 levels off and slowly falls.

As you know this is not a new issue. What is new is the growing weight of scientific support which raises the CO2-climate impact from speculation to a serious hypothesis worthy of a response that is neither complacent nor panicky.

But there were other currents mitigating against the sort of response Press calls for. “The story of climate policy in the US, generally, is one missed opportunities and unjustifiable delay,” said Jack Lienke, author of the book Struggling for Air: Power Plants and the “War on Coal.”

Many other issues may have seemed more pressing, or simply better understood. As Lienke writes in Struggling for Air, “At a time when Americans were still dying somewhat regularly in acute, inversion-related pollution episodes, it is unsurprising that legislators were more concerned with the known harms of sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide than the uncertain, seemingly distant threat of climate change.”

The authoritative National Academy of Sciences has just alerted us that it will issue a public statement along these lines in a few weeks.

That public statement, released later that month, emphasized the importance of shifting away from fossil fuel energy and highlighted the urgency of starting to transition to new energy sources as soon as possible: “With the end of the oil age in sight, we must make long-term decisions as to future energy policies. One lesson we have been learning is that the time required for transition from one major source to another is several decades.”

So what happened? When Press’s memo made it to the president’s desk, Jim Schlesinger, America’s first secretary of energy, also attached his own note in response:

My view is that the policy implications of this issue are still too uncertain to warrant Presidential involvement and policy initiatives.

Carter seems to have heeded this warning, and did not make much progress on climate crisis mitigation during his presidency. Yet he did sign some significant pieces of environmental legislation, including initiating the first federal toxic waste cleanups and creating the first fuel economy standards.

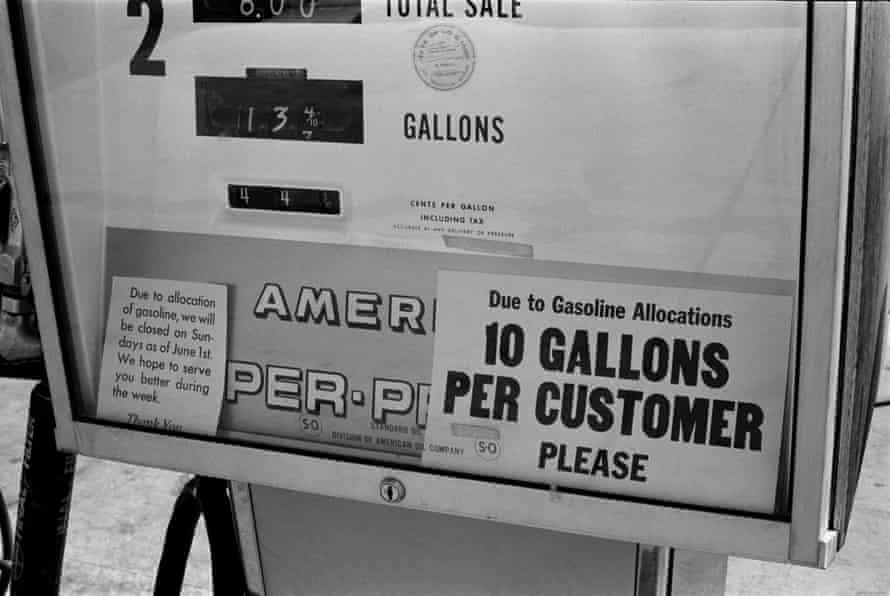

A significant challenge facing Carter was his own contradictory energy aims. Despite his goal of encouraging alternative energy, he also felt there was a national security interest in boosting US oil production in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis.

“We realized our dependence on foreign oil was dangerous and, very importantly, alternative energy was in its infancy,” Eizenstat said. “So Carter was both doing conservation and still encouraging more domestic oil and gas as a way of reducing dependence on foreign oil,” said Eizenstat. “As with all policy, you have conflicting goals.”

Still, it seems possible that if Carter had been re-elected, the world might have been in a better position regarding climate impacts today. One of the first things Reagan did after winning the election in 1981 was take down the White House solar panels. Meanwhile, the fossil fuel industry – whose scientists were already studying the ways that fossil fuels were changing the climate – started spending tens of millions of dollars sowing doubt about climate science.

Did the Press memo accomplish anything at all? For one person it was in fact a “transformational moment” – this was Eizenstat himself. He says it was instrumental in his own future work on the climate crisis, including his decision in 1997 to serve as the United States’s principal negotiator for the Kyoto global warming protocols.

Those protocols set the stage for the first international effort to tackle climate policy on a global level. So even if Press’s memo had a muted impact at the time, his warning wasn’t entirely ignored.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten

Opmerking: Alleen leden van deze blog kunnen een reactie posten.