How is this possible?' Researchers grapple with Covid-19's mysterious mechanism

Doctors are still exploring exactly how the coronavirus affects the body, and what its long-term impacts might be

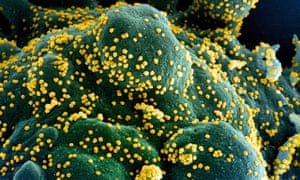

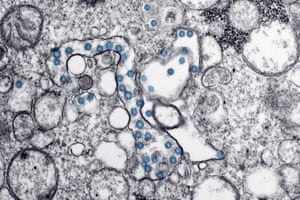

A colourised electron microscope image of a human cell heavily infected with coronavirus. Photograph: NIAID/NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH HANDOUT/EPA

A colourised electron microscope image of a human cell heavily infected with coronavirus. Photograph: NIAID/NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH HANDOUT/EPAMelissa Davey

Sat 2 May 2020 16.00 EDT

Respiratory physician Dr David Darley says something peculiar happens to a small group of Covid-19 patients on day seven of their symptoms.

“Up until the end of that first week, they’re stable,” says Darley, a doctor with Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital. “And then suddenly, they have this hyper-inflammatory response. The proteins involved in that inflammation start circulating in the body at high levels.”

In these patients, the lungs begin to struggle. Blood pressure lowers. Other organs, including the kidneys, may begin to shut down. Blood clots form throughout the body. The brain and intestines may also be affected. Some suffer changes to their personality, suggesting brain damage.

“I think what is evolving is a very specific set of stages of disease and for some reason, not everyone goes through all of the stages,” Darley says. “Some go through to the most severe stage and they require breathing support and oxygen. These patients who are severe tend to be older, they are more likely to be men, and also have other medical problems like diabetes, high blood pressure or cardiovascular disease.”

But there is no way of knowing which patients will be affected by the most severe symptoms. Clinicians like Darley hope that a disease biomarker – a unique characteristic in the blood, body fluids, or tissues – will eventually be discovered for each stage.

“It would help clinicians predict what stage patients are at and maybe even if they will progress to the next stage of disease,” he said. “It could help us predict who needs to be more closely observed in hospitals and would mean we have all the systems ready to go if they worsen. And it would give us more confidence to have them discharged to home if a biomarker says they are low risk for developing severe illness.”

Darley is one of the researchers working on a long-term St Vincent’s study of patients admitted to the hospital with Covid-19. Patients will be followed for a year after being discharged, receiving tests at regular intervals to see if there are any lasting effects or changes in the body’s immune system and blood. They will also be assessed for any ongoing changes to lung, gut and brain functions. No one yet knows if the virus causes permanent or long-term harm.

“I don’t think it’s clear yet whether it’s the virus infecting the lungs and the blood vessels, or if it’s the body’s immune system which goes out of control which then causes lung and blood vessel injury,” Darley said. “Or, it could be a combination of both.

“The pathogenesis is not clear yet. We are observing brain inflammation in a subset of patients, and in those we are seeing agitation and a change in behaviour or personality. That’s really interesting, and there are reports coming from elsewhere of some people, including younger patients, suffering stroke. It’s unclear whether the virus is infecting the lining cells of blood vessels in the brain, or whether the patient’s blood is excessively prone to clotting because of all the inflammation, leading to stroke.”

A renowned intensive care specialist from Italy, Prof Luciano Gattinoni, said this type of clotting in respiratory diseases is “extremely unusual”.

The 75-year-old has been working in intensive care for 40 years, and said he has never seen anything like what is happening to the lungs of some Covid-19 patients. What is particularly baffling is patients are presenting with poor oxygenation but little lung damage. This type of presentation is more typical of patients suffering from altitude sickness than a viral infection, Gattignoni says. As a result, patients who are very sick may not feel like they’re really struggling to breathe – even as they’re being critically deprived of oxygen.

“How is this possible?” Gattinoni told Guardian Australia from the intensive care department of the German hospital where he is working as a guest professor. “Bad oxygenation and good lungs tells me this must have something to do with the blood vessels. But these vessels are everywhere. In the brain. In the kidneys. So, in some patients, many organs are affected.”

The problem is, mechanical ventilation in intensive care replaces the strength of the respiratory muscles. If patients are struggling to breathe but their lung structure is OK, this ventilation does little to help and in fact may prove harmful, Gattinoni said, because mechanical ventilation is invasive.

He said while only a small number of patients are severe enough to require ventilation, a significant proportion of those on ventilators die, continuing to show low blood oxygen levels despite mechanical assistance.

Gattinoni said doctors must use ventilators only when needed, and at the right time. Getting this right can improve survival rates, he believes, and he thinks wrongly timed ventilation is why some intensive care units treating Covid-19 patients have higher death rates than others.

“Timing with this disease is absolutely critical,” he said. “Ventilation cannot begin too early or too late.” In the meantime, patients are given anticoagulants, drugs that prevent or slow blood clotting in the hope that stroke can be prevented.

Darley said scans of the lungs of Covid-19 patients are unique, showing “ground glass opacity”, a hazy pattern that does not obscure the underlying lung structure. Lung cancer, for example, would typically show on a scan as a dark, solid lesion, obscuring other structures in the lungs. While other illnesses, for example bacterial infections, can result in ground glass opacity on a scan, there were some unusual features on scans for Covid-19, Darley said.

“It has a classic pattern in Covid,” he said.

He suspects men are more severely affected than women because the virus is activated by an enzyme controlled by androgens, a group of hormones that play a role in male characteristics. But more research is needed to test this hypothesis. Darley added that any research into the virus needed to be conducted ethically and with strong scientific protocols.

“With no treatments for this virus, all we can do for severe patients at the moment is provide supportive care,” he said. “If the level of fluid is low, we can replace it. If they need ventilation, we can help them breathe. But treatments for this disease can only come from clinical trials.

“Our commitment at our hospital is to work with the highest level of scientific inquiry. People are desperate for treatments but we are reluctant to try treatments outside of clinical trials here.

“If we don’t clearly show a treatment is better than placebo or other treatments, we could be creating noise and adding to the current chaos of the scientific community. Our responsibility is to find treatments that work.”

Gattinoni agrees. He said scientists had been trying for decades to find drugs that moderate the inflammatory reaction, and he said these drugs had been “romanticised and popularised” in the race to find treatments for Covid-19.

“But in thousands of experiments over the years trying to block inflammatory responses, we’ve only had a lot of poor results,” Gattinoni said. “Like many other things in medicine, we have to be patient.”

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten

Opmerking: Alleen leden van deze blog kunnen een reactie posten.