\

The contested centenary of Britain’s ‘calamitous promise’

The British pledge to establish a ‘Jewish national home’ in Palestine is being celebrated and condemned as a divisive anniversary approaches.

By Ian Black

Tuesday 17 October 2017 01.00 EDT

On the evening of Thursday 2 November, at an elegant but as yet undisclosed central London location, Theresa May will sit down for a festive dinner with Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and 150 other carefully selected VIP guests. They will be celebrating the historic promise, made a century ago to the day, that the British government would use its “best endeavours” to facilitate the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Security for the event will be tight and protesters will be kept well away. This is no ordinary anniversary.

That 1917 pledge – known to posterity as the Balfour declaration – had fateful consequences for the Middle East and the world. It paved the way for the birth of Israel in 1948, and for the eventual defeat and dispersal of the Palestinians – which is why its centenary next month is the subject of furious contestation. After 100 years, the two sides in the most closely studied conflict on earth are still battling over the past.

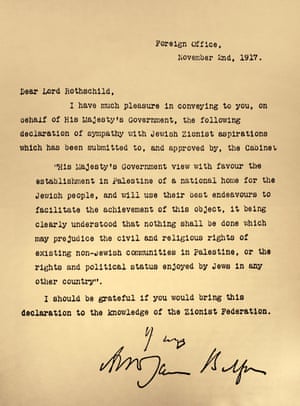

Controversy dogged the declaration from the moment that Arthur Balfour, then foreign secretary, sent it to Lionel Walter, Lord Rothschild, who represented the British Jewish community. Its 67 words combined considerations of imperial planning, wartime propaganda, biblical resonances and a colonial mindset, as well as evident sympathy for the Zionist idea – embodied in the famous commitment to “view with favour the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people” in the Holy Land. It ended with two important qualifications: first, that nothing should be done to prejudice the “civil and religious rights” of Palestine’s “existing non-Jewish communities.” And second, that the declaration should not affect the rights and political status of Jews living in other countries.

This contested anniversary is a dangerous minefield for May’s embattled government. The prime minister has said she is looking forward to it – although the London dinner, as all those involved are anxious to emphasise, is deliberately being hosted not by her, but by the current Lords Rothschild and Balfour. In addition to the two prime ministers and other political heavyweights, invitees include the historian Simon Schama, who will deliver a public lecture on the subject the day before. Scores of other events are being organised by Jewish communities across the UK. Christian Zionists, who believe in the unerring power of biblical prophecy, are to celebrate at the Albert Hall under the slogan “Partners in this Great Enterprise”.

Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, will hold a special session honouring Balfour, while British immigrants to the Jewish state are organising street parties to celebrate the day. In the US, the Israel Forever Foundation is urging supporters to “Stand with Balfour and make it YOUR declaration”. The original letter, kept in the British Library, may be loaned to Israel next year to mark the 70th anniversary of the country’s independence. In 2015 it was inspected by a reverential Netanyahu, who used the photo opportunity to call for a renewal of the “partnership” of 1917. (Netanyahu’s official residence, incidentally, is on Balfour Street in West Jerusalem. The address is used in the Israeli media, like Downing Street in Britain, as shorthand for its occupant.) A copy of Balfour’s letter is also on permanent display at the Yasser Arafat Museum in the West Bank town of Ramallah, seat of the Palestinian Authority and, since the 1967 war, occupied territory under international law.

In London, Jerusalem and elsewhere, however, others will be commemorating and protesting what they condemn as an act of betrayal and perfidy, the “original sin” that led to injustice, war and disaster for the Palestinians in the Nakba (Arabic for “catastrophe”) of 1948. Two packed conferences took place on the same day in London in early October, with speakers lambasting British responsibility for continuing Palestinian suffering.

The Balfour Project – founded by clergymen and academics who want to see change in the UK’s Middle East policy – is holding a public meeting in Westminster on 31 October. Its slogan is: “Britain’s Broken Promise – Time for a New Approach”. But concern for the plight of the Palestinians is no fringe preoccupation. The former UN envoy to Syria, Lakhdar Brahimi – one of the Elders, a group of world leaders founded by Nelson Mandela in 2007 – is the biggest name on a Chatham House panel on Balfour. The British Academy is organising a seminar about the decision, which was described by the historian Elizabeth Monroe in the 1960s as “one of the greatest mistakes of our imperial history”. A London art gallery is running a series of events called “Turning the Page on the Balfour Declaration”, focusing on Arab culture and identity in Palestine before 1948. The centenary was debated in the House of Lords in July.

In an age when the conflict is increasingly waged by volunteer armies of social-media warriors, it should come as no surprise that both sides are determined to press their competing claims. The Balfour Apology Campaign is demanding Britain make amends for “colonial crimes” in Palestine. It is promoting a short film, 100 Balfour Road, which tries to explain the long-term effect of the declaration by showing the Joneses, an ordinary family in suburban London who are evicted from their home by soldiers and forced to live in appalling conditions in their back yard. Another family, the Smiths, take over their house and, supported by the soldiers, mistreat the Joneses and deprive them of food, medicine and their basic rights. The dissident group Independent Jewish Voices has produced a critical talking-heads documentary about Balfour – being circulated under the Twitter hashtag #NoCelebration.

For the past year, the Palestinian mission to the UK has been running its own campaign around the centenary, titled “Make It Right”, to demonstrate that “the legacy of the British government’s broken promise still continues”. This month, the Palestinians attempted to place adverts on the London underground and buses, citing Balfour’s qualification about “the civil and religious rights of non-Jewish communities”, alongside before-and-after pictures highlighting Palestinian suffering since 1948. But Transport for London blocked the ads on the grounds that the issue is too sensitive and controversial. Manuel Hassassian, the Palestinian Authority’s ambassador to the UK, has complained of “censorship”.

In Jerusalem on 2 November, separate Palestinian and Israeli Balfour conferences are being held – completely ignoring each other – on the eastern and western sides of what Israeli governments call the country’s “united” capital. In the UK, a national march and rally will be staged on 4 November by the Palestine Solidarity Campaign and the Stop the War Campaign. History is alive, toxic, intensely political and bitterly divisive – and it will be revisited with passion and anger on this resonant anniversary.

The battle over Balfour has much in common with other disputes over historic apologies or redress for the wrongs of the past. It may be seen alongside recent rows over the Cecil Rhodes statues in Oxford and Cape Town and Confederate memorials in the US, compensation for British mistreatment of Mau Mau rebels in Kenya and French atonement for atrocities in Algeria. But the Israel-Palestine issue is far harder to deal with. Its past is not another country. Truth and reconciliation, let alone closure, are remote fantasies. Unlike slavery, apartheid, the Irish famine and western colonialism – all, at least formally, consigned to the dust heap of history – the Arab-Jewish conflict between the Mediterranean and the River Jordan shows no signs of fading. Indeed, it remains as bitter as ever, stuck in a volatile status quo of unending occupation and political deadlock.

Arthur James Balfour has always been a hero to Zionists and a villain to Arabs and their respective supporters. The brief document that bears his name is seen as marking the beginning of what is today widely considered the world’s most intractable conflict. On that, if on little else, Israelis and Palestinians agree. The central issue is that when the declaration promised that “Jewish national home”, what it defined as Palestine’s “existing non-Jewish communities” – who remained unnamed – made up some 90% of the 700,000-strong population. The words Arab, Muslim or Christian were not mentioned. Nor were those natives consulted as to the future of their country, which was then made up of three provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Their “civil and religious rights” in fact counted for little.

The anniversary has been marked by Arab protests since the very first one in 1918. In 2004, when president George W Bush issued a statement that reversed decades of US policy by stating that Israeli settlements in the occupied territories could stay put, the Palestine Liberation Organisation compared it to Balfour’s declaration – which has been traditionally described in Arabic as a “calamitous promise”.

“For Palestinians, the Balfour declaration is the root cause of our destitution, dispossession and the ongoing occupation,” the Palestinian mission to the UK told the Commons foreign affairs committee in April as it gathered evidence for an inquiry into British policy towards the Middle East peace process. “The centenary … allows us to take the long view. Our present reality is a consequence of a British policy that created Israel at the expense of the Palestinian people.”

At a recent film festival in Gaza – ruled by the Islamist movement Hamas – attendees walked up a red carpet that had been imprinted with quotations from the declaration. In Ramallah this February, a day after the Knesset voted to retroactively legalise West Bank Jewish settlements, which are seen by most of the world as illegal, I interviewed Hanan Ashrawi, the veteran Palestinian spokesperson and legislator, who described the ongoing occupation as a natural consequence of the 1917 declaration. “This is Balfour’s chickens,” she said, “coming home to roost.”

The declaration, Ashrawi said, “didn’t create the state of Israel, but it set in motion a process by which Zionism was adopted internationally. It is an outcome of a colonial era and it belongs to that era in many ways – the European white man’s burden of trying to reorganise the world as they saw fit, to distribute land, to create states. They defined us as the ‘non-Jewish communities’. It’s so patronising, so racist.”

By contrast, Israel and its supporters like to remember a magnanimous British gesture towards a persecuted people who were yearning, according to the Zionist narrative, to “return” from exile to their biblical homeland – even though, in the three decades before the first world war, the vast majority of east European Jews who were able to were heading west to that far more promising land, the US. (Britain’s self-interested motives are acknowledged too, and there is an awareness, on what remains of the Israeli left, of the stigma of colonialist patronage.)

Yet not only is there nothing to be sorry about, many insist, but to demand an apology is an act of antisemitism; to question the justice of the declaration, it is argued, is to question the right of the Jewish people to self-determination in a century that saw a third of them exterminated by the Nazis. “The Palestinians’ new campaign to highlight the ostensible illegalities and iniquities of the Balfour declaration,” David Horowitz, the editor of the Times of Israel, has written, “shows an undimmed hostility to the very notion of Jewish sovereignty anywherein the holy land, and an abiding refusal to accept Jewish legitimacy here.”

Netanyahu uses similar language – stating ever more explicitly, especially since the Donald Trump era began, that a Palestinian state worthy of the name will never be created. His government is the most rightwing in Israel’s history. The “peace process” has been clinically dead for three years, and moribund for several more. Pro-Palestinian activists are using the centenary to step up the international campaign for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS), many of whose supporters characterise Israel unequivocally as an apartheid settler state, and whose modest successes so far have alarmed many Israelis and Jews. Others, including the UK’s Balfour Project, are adamant that they are not questioning the legitimacy of Israel, but working for Palestinian rights and a two-state solution. But a middle ground is hard to find when the mainstream positions of the two sides on this question are so very far apart. “God did not give you the land,” protested one pro-Palestinian Twitter message this month. “The UK did – illegally.”

The most memorable line about the Balfour declaration was composed by the Hungarian-born Jewish writer Arthur Koestler. With it, he quipped, “one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a third” – an echo of the popular early Zionist slogan that depicted Palestine as “a land without a people for a people without a land”. Questions about exactly what constituted a nation or people, Palestine’s identity and borders and how these related to Britain’s other wartime promises have occupied historians – and propagandists – ever since. Avi Shlaim, emeritus professor of international relations at Oxford and a leading expert on the Arab-Israeli conflict, has described Balfour as “a millstone round Britain’s neck” because it prompted the wrath of both dissatisfied or impatient Zionists and angry Arabs and Muslims. Jonathan Schneer, an American historian, has called the pledge “the highly contingent product of a tortuous process characterised as much by deceit and chance as by vision and diplomacy”.

There has long been debate over the intentions and meaning of the declaration. David Lloyd George, the Liberal prime minister at the time, highlighted sympathy for Jews and his own Welsh nonconformist familiarity with the Old Testament. But British motives in the penultimate year of the first world war, following the February revolution in Russia and America’s entry into the conflict, were mixed. The decisive considerations were the wish to outsmart the French in the postwar Levant, and to use Palestine’s strategic location to protect Egypt, the Suez canal and the route to India by creating “a loyal Jewish Ulster”, in the words of Ronald Storrs, the first British military governor of Jerusalem.

Other scholars have placed greater emphasis on the need to mobilise Jewish public opinion behind the flagging allied war effort. Balfour told the cabinet: “If we could make a declaration favourable to such an ideal [Zionism], we should be able to carry on extremely useful propaganda both in Russia and in America.” This approach, as modern researchers have observed, wildly exaggerated Jewish wealth, power and influence – a familiar antisemitic habit. Balfour, as Conservative prime minister, had, after all, backed the 1905 Aliens Act, which severely restricted Jewish immigration. Anti-Zionist critics like to point out that he never proposed a national home for oppressed Jews in his native Scotland; he was “uncertain and uncomfortable about their place in gentile society,” reported Leonard Stein, who published the first serious study of the declaration.

Questions continue to be asked about the connections and contradictions between Balfour’s public statement of support for Zionism; the secret 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement between Britain, France and Russia to carve up Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq; and earlier secret pledges about Arab independence made by the British to encourage Sharif Hussein of Mecca to launch his “revolt in the desert” against the Turks (with the help of TE Lawrence “of Arabia”). The truth, buried in imprecise definitions, misunderstandings and duplicity, remains elusive. But Britain’s own wartime interests, in any event, were the absolute priority.

Arab views were blunt from the start. The Balfour declaration, argued the Lebanese historian George Antonius, betrayed the understandings between Sharif Hussein and Sir Henry McMahon, Britain’s high commissioner in Egypt. And these in turn were contradicted by Sykes-Picot, under which much of Palestine was to be under international administration. Britain’s promise to the Zionists, Antonius wrote in his 1938 book The Arab Awakening, “lacks real validity, partly because she had previously committed herself to recognising Arab independence in Palestine, and partly because the promise involves an obligation which she cannot fulfil without Arab consent”. If the first point – often summarised as “the twice-promised land” – was debatable, the second was not. Arabs had not consented; they felt, then as now, that they had been cheated.

Balfour’s carefully drafted formulation was also studiously vague – a diplomatic “fudgerama” in the words of the current foreign secretary, Boris Johnson. It neither defined the legal meaning of a “national home” nor promised to create a Jewish state. And that vagueness encouraged Palestinians to hope that Britain’s policy would not be pursued. Chaim Weizmann, the Russian-born Zionist leader whose charm and assiduous lobbying were instrumental in securing the declaration, was disappointed with its final wording. “I did not like the boy at first,” he wrote. “He was not the one I had expected. But I knew this was a great event.”

The key fact was that the world’s greatest power had given a massive boost to the Zionist movement 20 years after its birth – against the background of Russian pogroms and the Dreyfus affair in France. In a mood that is often described as “messianic”, Balfour was hailed as a “new Cyrus” – the Persian king who liberated the Jews from their Babylonian exile in the sixth century BC. “There was a great stirring of the dry bones of Israel,” one Zionist wrote, “as if in realisation of the prophetic vision of Ezekiel.”

The Manchester Guardian gave the declaration an effusive welcome. CP Scott, its editor, had introduced Weizmann to Lloyd George; his editorial invoked the memory of the recent massacres of the (Christian) Armenians by the (Muslim) Turks, as well as reflecting contemporary colonialist assumptions. Jews needed a national home for their security, wrote Scott, calling Balfour “the signpost of a destiny”.

Arabs in Palestine reacted with alarm. The country’s native Jews were predominantly Orthodox, and enjoyed religious autonomy under Ottoman rule. But the demographics of the Jewish community had begun to change with the arrival of the first Zionist settlers from Europe in the 1880s. In 1910, an Arab writer fretted that Jews in Haifa were starting to interact exclusively with their own community. “Establishing a Jewish state after thousands of years of decline … we [Arabs] fear that the new settler will expel the indigenous and we will have to leave our country en masse. We shall then be looking back over our shoulder and mourn our land as did the Muslims of Andalusia,” Abdullah Mukhlis warned in a remarkably prescient article. “Palestine may be endangered. In a few decades it might witness a struggle for survival.”

The new reality of British rule arrived on 11 December 1917, when General Sir Edmund Allenby walked through the Jaffa Gate into Jerusalem’s Old City. “Palestine is Arab”, a newly created nationalist association declared. “Its language is Arabic. We want to see this formally recognised. It was Great Britain that rescued us from Turkish tyranny and we do not believe that it will deliver us into the claws of the Jews. We ask for fairness and justice. We ask that it protect our rights and not decide the future of Palestine without asking our opinion.”

British officials ignored such appeals, though some quickly recognised what was happening. “It is indeed difficult to see how we can keep our promises to the Jews by making the country a ‘national home’ without inflicting injury on nine-tenths of the population,” one wrote in 1920. “But we have now got the onus of it on our shoulders, and have incurred odium from the Moslems & Christians, who are not appeased by vague promises that their interests will not be affected.” In 1922, Balfour’s pledge was incorporated into the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine, setting out the terms for Britain’s administration – what the new body called a “sacred trust for civilisation”. Promotion of Jewish immigration and the revived Hebrew language were key commitments. The word “Arab” did not appear in it.

Early Arab opposition to Zionism was often described as an “unseen question”, and it was frequently suggested that the Palestinians had no national identity before the arrival of the first Jewish settlers. But both the British and Zionists were acutely aware of local objections from the start. “Even if all our political schemings turn out the way we desire, the Arabs will remain our most tremendous problem,” Weizmann’s colleague Harry Sacher worried in June 1917. “I don’t want us in Palestine to deal with the Arabs as the Poles deal with the Jews, and with the lesser excuse that belongs to a numerical minority.” Zionists believed fervently in their “right to national rebirth” in Eretz-Yisrael (“the land of Israel”) – from where their ancestors had been exiled by the Romans in AD70. Earlier efforts to secure recognition from the Turks had failed. Balfour mattered because the alliance with Britain allowed them to exercise that right. And there was wider support – contrary to Koestler’s clever “one nation” quip – from the US, France, and Italy.

The League of Nations mandate, five years after Balfour, provided the first international legal framework for Zionist ambitions – ignoring Palestinian objections and setting a pattern that would be repeated in the future. Britain’s recognition also helped the Zionist movement evolve from an insignificant minority in world Jewry to one that attracted growing sympathy. Objections by Jews to Zionism started to fade once the mandate was in place – though it took the horrors of the second world war for them to all but disappear. Arab opposition never weakened.

Balfour showed no regrets. In 1919 he famously told his cabinet colleague, Lord Curzon, who had expected the declaration to cause trouble for Britain, that “Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-old traditions, in present needs, in future hopes of far profounder importance than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land”. This brutally candid display of partiality – “dripping with Olympian disdain” in the words of the veteran Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi – still arouses Arab anger.

The aftermath was marked out by sombre milestones, each representing further escalation. Arabs attacked Jews in 1920 and 1921. In 1925 Balfour, now retired, visited Palestine, where he was feted by Jews – who named a new settlement in the Jezreel Valley (Marj Ibn Amr in Arabic) after him. Arabs shunned him. Four years later came new disturbances in Jerusalem: the focus, then as now, was the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount, site of the al-Aqsa mosque. The worst bloodshed, though, was in Hebron, where Arabs killed 67 defenceless Orthodox Jews who were not part of the Zionist camp – though that old distinction was rapidly disappearing. Three of the 1929 killers were hanged by the British in Acre jail – and are still hailed in a popular song as “martyrs” to the Palestinian cause.

On 2 November 1932, by now a familiar date, the Arabic newspaper Filastin devoted its front page to a cartoon picturing Lord Balfour dominating a map of the country, clutching his “calamitous promise”. It displayed “the woes inflicted on Palestine” – the advances of Zionism under the protection of the British, represented by a haughty officer in riding boots and a warship moored off Haifa. It shows Jewish immigrants striding energetically towards Tel Aviv, passing a glum-looking Arab peasant family on a camel, evicted from their land and plodding towards the desert. The scenery is dotted with factories, mechanised agriculture and bustling public works – all Jewish achievements. In the corner stand Arab men in European suits and tarbushes, arguing (presumably ineffectively) about the transformation they are witnessing. Sir John Chancellor, British high commissioner until shortly before, reflected that Balfour had been “a colossal blunder”. Events elsewhere, however, were soon to mean that it was too late to do very much about it.

In the mid-1930s, with the spread of antisemitic legislation in eastern Europe and Hitler’s rise to power, came a massive wave of immigration – of refugees who were also settlers – doubling Palestine’s Jewish population. In the wake of the Arab rebellion in 1937 – Balfour’s 20th anniversary – Britain’s Peel Commission, which was established to look at the cause of the violence, acknowledged the “irreconcilable aspirations” of the two peoples. It proposed partitioning the country into Jewish and Arab states, but retreated from the idea as a new war approached. Only in 1939 did Britain change policy, severely restricting Jewish immigration and land sales, and promising Palestinian independence. “The framers of the Mandate in which the Balfour Declaration was embodied could not have intended that Palestine should be converted into a Jewish State against the will of the Arab population,” stated that year’s white paper. “His Majesty’s government … now declare unequivocally that it is not part of their policy that Palestine should become a Jewish state.” The Jews, outraged, rejected this – many now viewing the British as their enemy. But so, foolishly, did the Arabs, missing a last chance to salvage something from what the Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi has called the “iron cage” of the mandate and the wreckage of the preceding two decades.

By the declaration’s 30th anniversary, in November 1947, in the wake of the Holocaust, public opinion outside the Arab and Muslim world backed the creation of a Jewish state. Even as the Royal Navy was turning back Jewish refugees trying desperately to reach the shores of Palestine, and Irgun and Stern Gang terrorists were targeting the British, the Jewish population had reached a third of the total. In the US in particular, Zionists were seen as progressives, fighting both British imperialism and its reactionary Arab lackeys. In those early cold war days, the US and USSR both supported that month’s UN plan to partition the country into separate Jewish and Arab states. It was rejected by the Palestinians, because they refused to surrender to what they saw as foreign settlers who had transformed the country while ignoring them. It was another error – though arguably an understandable one. Israel’s independence became the Palestinians’ catastrophe – the Nakba – in which half the country’s Arabs were driven out or fled. Arab Palestine was erased by Israel and Jordan. The UN’s decision would not have taken place without the British one in November 1917. Balfour remains a byword for the legitimacy of Zionism, and for the calamity that it brought the Palestinians. It is hard to imagine that changing.

Preparations for the centenary have posed a difficult challenge for the British government. It continues to emphasise support for a two-state solution to the conflict, a position that dates back to the late 1980s, though its roots can be traced to 1967, when Balfour’s jubilee was overshadowed by the six-day war. Israel’s stunning feat of arms that year meant that all of Mandatory Palestine – as well as the Egyptian Sinai peninsula and Syria’s Golan Heights – was re-reunited under its rule. Military victory, though, turned out to be the easy part.

The timing created a neat and thought-provoking link between two towering historical landmarks: the first political triumph of Zionism, and the beginning of an occupation that would, over the years, undermine it and threaten to isolate Israel. “If the Balfour declaration represents the moment the goal of Jewish statehood first gained formal international recognition and legitimacy, 1967 was the moment when the recognition and legitimacy started to ebb, gradually giving way to 50 years of growing unease,” Jewish-American journalist JJ Goldberg wrote this summer. “Put differently, the Balfour declaration launched a diplomatic process that led to an international embrace of what had been up to then a crazy dream of Jewish national rebirth. The six-day war touched off a series of events that may yet end in the dream’s demise.”

It was then that the Palestinians, remembered since 1948 only as “Arab refugees,” returned to centre stage. Resistance to occupation or terrorist acts such as the Munich Olympics massacre of 1972 made headlines. Sympathy for them grew with the Lebanon war of 1982. But the Israelis were only seriously challenged in 1987, by the first intifada – the “war of the stones” – when the world saw Palestinian children confront Israel’s armed might. That was followed by Yasser Arafat’s unilateral declaration of Palestinian independence, which paved the way for the 1993 Oslo agreement. Oslo was killed off – after the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin – by settlement expansion, bad faith, suicide bombings and a second, armed intifada that erupted disastrously after the collapse of the Camp David summit in 2000. Arafat’s death in 2004 marked a nadir for the Palestinian cause. Little has changed since he was succeeded by Mahmoud Abbas, though the Hamas takeover of Gaza in 2007 was deeply divisive. In 2012, when Abbas secured UN observer status for Palestine, the UK refused to follow the 136 other countries which had recognised it, standing loyally by the US.

Last year the government’s initial public line, after nervous consultations in Whitehall, was awkwardly defensive: Britain would simply “mark”, not “celebrate”, Balfour because the declaration was flawed in not backing political rights for Arabs as well as Jews. But Britain would not apologise. To do so, ministers told Manuel Hassassian, the Palestinian ambassador, would open a Pandora’s box of demands about Cyprus and Kashmir and other festering imperial wounds. “It can’t be all bells and whistles to support Israel, but nor can it be complete sackcloth and ashes and let’s hear it for those who would recover Palestine,” one well-placed politician told me. “It’s about finding a line between those two.”

The aftermath of the EU referendum in 2016 brought a small but significant change in Britain’s public stance. May, attempting to think more “globally” after the Brexit vote and Trump’s election victory, criticised Barack Obama’s secretary of state, John Kerry, for his warning that the expansion of Israeli settlements was leading to “one state and perpetual occupation”. Kerry’s remarks followed the passage of UN security resolution 2334, which reiterated that Israeli settlements were illegal under international law – and which was backed by the UK and, unusually, not vetoed by the US. That was widely seen as a frustrated Obama’s parting shot and an attempt (so far in vain) to “Trump-proof” US policy.

May was scorned for trying to curry favour with the incoming president. Soon afterwards she invited Netanyahu to London for the Balfour centenary, and added that Britain would mark it “with pride” – two words that attracted disproportionate attention, as ever with this most sensitive of subjects. And that remains the current official mantra – albeit muttered sheepishly by embarrassed FCO officials.

The official UK response to the demand for a Balfour apology – which had been supported by 13,600 people who signed a petition to parliament – was released this April. “We are proud of our role in creating the state of Israel,” it said. “Establishing a homeland for the Jewish people in the land to which they had such strong historical and religious ties was the right and moral thing to do, particularly against the background of centuries of persecution.” Alistair Burt, minister for the Middle East, has quietly compromised since then by talking of “pride and sadness”.

Brexit also killed off the ongoing investigation by the Commons foreign affairs committee into UK policy towards the conflict. The FAC, as the rules require, was dissolved along with parliament when the election was called. Its chairman, Crispin Blunt, had hoped to publish his report on 2 November – for symbolic reasons – and had been expected to challenge government positions. Blunt was unpopular with Israel and its supporters. His replacement, Tom Tugendhat, is far closer to Israeli views and emphasises wider regional instability. The Arab spring and its bloody aftermath, he has suggested, “showed that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict doesn’t matter”. There is said to be “no appetite” to reopen the FAC investigation on his watch.

Sir Vincent Fean, the former British consul-general in East Jerusalem, and a supporter of the Balfour Project, never believed that an apology for Balfour was worth pursuing, preferring to call for UK recognition of Palestine. “Recognition means that when Abbas or whoever comes after him next applies to the UN for full membership, the UK will vote yes,” he argues. “That will put us in a different part of the forest from the US, and it does strengthen the argument that there should be consequences for breaches of international law. It could cause other EU members to think hard about doing it, too.” Foreign Office officials insist, however, that recognition will not happen until or unless it can help advance peace – leaving unsaid that a decision of that magnitude is, of course, for Washington to make. Still, resentment at the UK attitude may yet produce a pre-centenary parliamentary statement that at least reiterates support for a Palestinian state alongside Israel.

In the multilateral, post-colonial world of 2017, Britain no longer has the power – for good or ill – to issue unilateral declarations that are intended to serve its interests but have a massive influence on other peoples who are not consulted. The clock cannot be turned back. It is impossible to conceive today – joking apart – of a “Johnson declaration” that could have even a fraction of the impact of the one made by Balfour.

In recent years, the UK consulate in East Jerusalem has been helping Palestinian farmers harvest their olives in vulnerable areas of the West Bank that are affected by Israeli settlements – emphasising that practical assistance is more useful than symbolic gestures or apologies. Still, it does not appear that Britain’s “best endeavours” – at a time when its international clout is weakening – can do much to help resolve the enduring conflict it helped create a turbulent century ago.

Ian Black is the Guardian’s former Middle East editor and diplomatic editor. His new book, Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017, is published by Allen Lane on 2 November in the UK, and by Grove Atlantic on 7 November in the US. Buy it for £21.15 at bookshop.theguardian.com

•

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten

Opmerking: Alleen leden van deze blog kunnen een reactie posten.