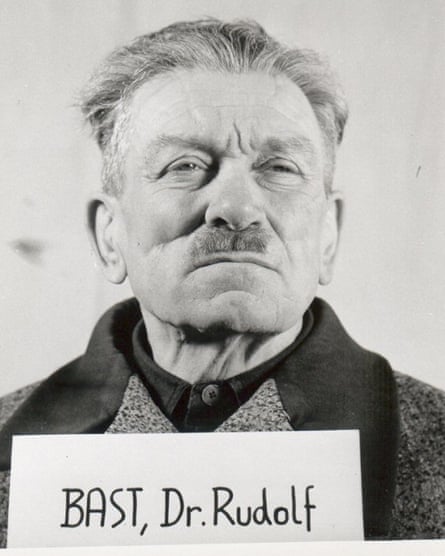

SS officer Gerhard Bast, scarred from duelling, in June 1944. Photograph: Courtesy of Martin Pollack

My father did terrible things during the second world war, and my other relatives were equally unrepentant. But it wasn’t until I was in my late 50s that I started to confront this dark past

M

The official postwar version of events stated that Austria had been the first victim of Hitler’s expansionist politics. The four victorious allies – Britain, France, the US and the Soviet Union – specifically approved this interpretation, which, some believe, got Austria and Austrians off the hook for their complicity in Nazi atrocities.

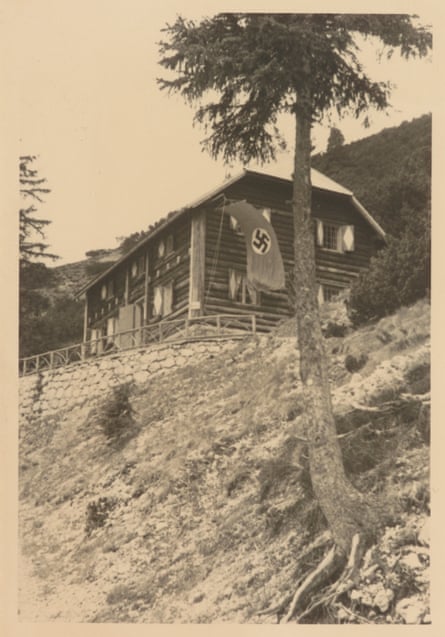

But not all Austrians accepted this version. Large parts of Austrian society still felt strong ties to national socialism, an aggressive Greater German ideology that rejected the notion of Austria as a separate country with its own history and mentality, and cultivated a deeply rooted antisemitism and anti-Slavic sentiment. My family, like many others, held on to their belief in Hitler and the Third Reich until they died. “We are not Austrians but Germans,” was the oft-repeated credo fed to me as a child. “And we will forever be proud of it.”

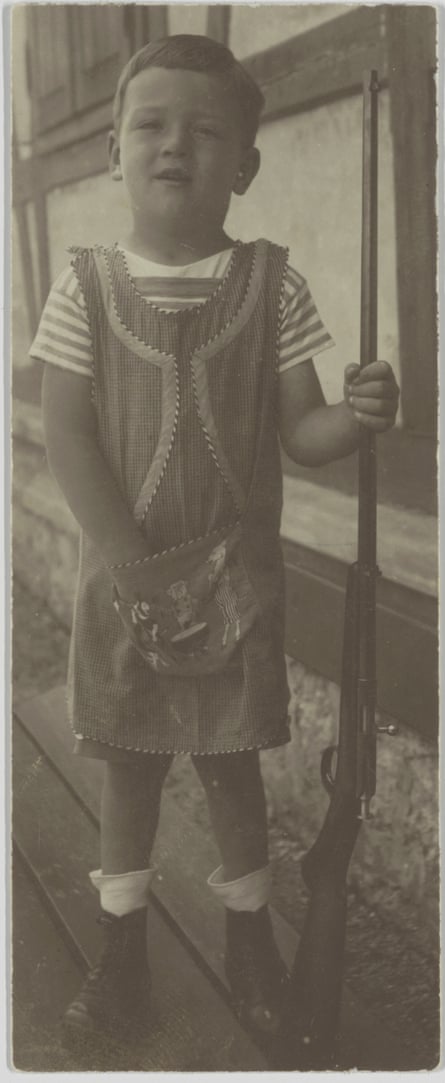

I was born in 1944, a year before the end of the war. When I was 10 I was sent to boarding school, far away from Linz, where I had lived with my mother and stepfather, and from Amstetten, where I had often stayed with my Nazi grandparents. Why my relatives sent me away is still a mystery to me. Maybe they were attracted by the fact that the school was high up in the mountains, surrounded by woods, far from the corrupting influence of the cities, from the Jewish, anti-German spirit, as my grandmother put it. Another bonus was that we had to learn a trade in school – I became a carpenter.

What they didn’t know was that the school was very liberal in spirit. Not a single teacher was an old Nazi, which was an exception in Austria in the 50s. As I spent most of my time in school, I was removed from the influence of my Nazi relatives, and soon began to doubt the wisdom of their beliefs, their Great German ideas, their antisemitism and hatred for Austria and democracy. In school, we were taught other beliefs.

My mother had married Hans Pollack, a man 20 years older than her, in about 1930. I was never told that he was not my biological father, but I gradually became aware of it. I was regularly sent to Amstetten to stay with grandparents, who welcomed me with open arms as their boy Gerhard’s son. My sister and brother in Linz, who were older than me, never went to Amstetten. They didn’t even know my grandparents there. A strange, confusing situation – but I just accepted it.

I remember when my mother told me for the first time that my real father’s name was Gerhard Bast, and that he had been an officer of the SS and a leading member of the Gestapo. I was 14, old enough to understand what that meant. She didn’t tell me what he had done during the war – maybe she didn’t know herself, at least not in detail. He had died in 1947, when I was three. Learning all this, I experienced a shock. I was totally confused and had no idea how to react. I had nobody with whom I could discuss my feelings, not even my schoolmates – they were compassionate, but didn’t really understand my situation. So I had to come to terms with the horrible news by myself. It took me a long time, but I managed somehow to carry on with what might be called a normal life.

By the mid-1960s, I had ceased all contact with my family and was studying in Vienna. Out of the blue, my uncle got in touch to say my grandmother was dying. He asked me to come to Amstetten, an hour and a half by train west of Vienna. I rushed to see her one last time. She had been the best grandmother imaginable – she loved and pampered me without limits. But she was also a stubborn, tough woman. And a Nazi to her very core. I came too late. My uncle greeted me at the door with the words: “She died like a German woman.” I realised then that the family hadn’t changed one iota. Nor would they.

I

In the late 19th-century, hostilities and clashes between Germans and ethnic Slavs were frequent. My grandfather and two of his brothers were sent to Graz to study. They had already absorbed a militant German nationalism at home: in Graz they joined Germania, a German fraternity (Deutsche Burschenschaft) characterised by a strong racial antisemitism and anti-Slavism.

The student Burschenschaften were nurseries of violent German nationalism. Run through with what today is called toxic masculinity, their members engaged in duelling, drinking, brawling and, after Hitler entered Austria in 1938, brutal and sometimes murderous attacks on Jewish and socialist professors in universities across Austria. Graz was considered a bulwark against the imagined onslaught of Slavs – Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.

The aftermath of the first world war had deepened the fears of my family that Germans would soon be overrun by a hostile majority of Slavic Untermenschen planning to rob the hard-working Germans of their rights and positions. Today, rightwing politicians across Europe accuse migrants of exactly the same. Conspiracy theories such as “the great replacement” remind me of claims I heard in my childhood. My family instilled in me the idea that we were the true victims upon whom Jews and Slavs preyed.

Nowadays, we see this offender-victim role-reversal all around us. Vladimir Putin and his followers constantly claim that they never planned an aggression against Ukraine, but were always on the defensive against the enemies that surround them: a western alliance still seeking to destroy a peaceful Russia in the hope of fulfilling Hitler’s original aims. That’s why Putin constantly rails against fictitious Nazis ruling Ukraine. Putin’s narrative has been increasingly adopted by the far-right across Europe, not least in my country by Austria’s Freedom party, the FPO, which won the greatest number of votes in June’s European parliamentary elections.

Almost 80 years after the end of the war, how is it possible that such strong echoes of national socialism remain apparently attractive? Why are people, living in peaceful times, in a democracy with all its benefits, planning to undermine and destroy that very system while aiming to revive the ideology and methods of the past? Hate speech, xenophobia, racism, thoughts of the superiority of a master race, the admiration of a strong man, a Führer, who rules with an iron fist, are gaining ground as if nazism had never happened. This afflicts not only Germany and Austria, but also other countries, including those with deeply embedded democratic traditions.

Is this a sign of some kind of collective amnesia? Are we, the children of Nazis, in some way responsible? Were we too complacent, thinking that democracy would survive without us actively fighting for it? I sometimes think my family members would have become admirers of Putin and his ilk. They were convinced that democracy was poison and only a strong man can save us.

I

Following in my grandfather’s footsteps, my father studied in Graz and like him joined the Germania fraternity, which after the first world war became even more radical. In 1931, at 20, he became a member of the Nazi party, and at the same time, joined the SS, at this point a small organisation of thugs always ready to fight their political adversaries – socialists, communists, Christian socialists or the police. Spurred on by the fraternity’s hard drinking and passion for duelling, my father got to know a new circle of friends, including Ernst Kaltenbrunner, later chief of the Reich security main office, a leading perpetrator of the Holocaust.

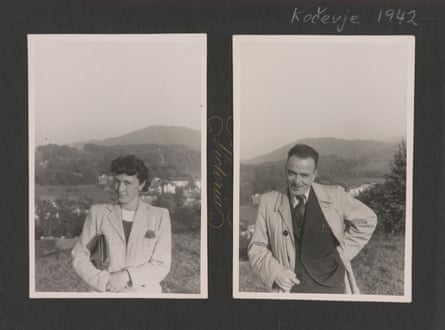

After the Anschluss in 1938, when Hitler’s troops marched into Austria and absorbed the country into the German Reich, my father got a job in the Gestapo in Graz. He seemed an ideal candidate, a convinced Nazi since before Hitler seized power. He had been imprisoned for his anti-Austrian activities, the same as my grandfather, a sure-fire recommendation for a career in the Gestapo, the SS and its intelligence agency, the SD. After Graz he was assigned to different German cities. In January 1941, he was sent to Linz, where he became acting chief of the Gestapo.

Linz was not any old Austrian city. Hitler had lived some years there in his youth, and remained sentimentally attached to the place. He went to school in Linz, albeit with little to show for it. One of his schoolmates was the man who would later become my stepfather, Hans Pollack, who remembered Hitler very well. Once he told my family about a school outing for his class and Hitler’s, who was one class above. They passed a meadow with high, dried grass. Hitler set fire to the grass, then climbed a tree to hold a flaming speech to his schoolmates, who were not impressed, but thought he was mad.

My father had many duties as a chief of the Gestapo. He was responsible for the enforcement of Nazi laws against forced labourers, any so-called enemies of the Reich and, of course, Jews. No case seemed too small to escape his attention. A friend of mine, a historian, came across the tragic story of an old man living near Steyr. This man was the only Jew in the village. Born in 1868 in Bohemia, Max Gorge moved to Austria, where he found employment as a linen weaver. When he retired, he lived in the town of Gaflenz. A poor old man hardly able to make ends meet. But he was not overlooked by the Nazis. In his files my friend found a letter signed by my father asking the authorities to register and report all Jews, without exception. Gorge was sent to Vienna in early 1942, and from there presumably to a death camp, but not before he had been punished with two weeks in prison because he had neglected to add the first name “Israel” in his papers.

Would Gorge have survived without the intervention of my father? I doubt it, but this is not the point. My father had in effect signed his death sentence. One might ask if it’s really worth delving into such a seemingly unimportant case. Weren’t there countless cases of mass murder, of millions killed in concentration camps or the killing fields in eastern Europe? Indeed, my father was also involved in mass murder by his own hand. But I still think individual cases like Gorge’s are important, because they prepared the ground and the spirit for what came later.

Nobody had forced my father to join the Gestapo and SS. He did it of his own free will, knowing what would be expected of him. He could have chosen another way. He could have become a lawyer like his father and his uncle – they were also involved in crimes, but not on the same level. So why? I have often asked myself this question, but never found a satisfactory answer. He was not a monster, a sadist, but a good friend, comrade in mountaineering and hunting, beloved of my mother. An ordinary man. There were many like him.

Of course his deep involvement in the murderous Nazi regime was partly an outcome of his upbringing, but this doesn’t minimise his guilt. He knew what he was doing. He had studied law and learned to distinguish between right and wrong. But people with moral qualms never rose to a position such as head of the Gestapo in Linz.

In a strange twist, my father’s career in the secret police came to an abrupt end in November 1943. As chief of the Gestapo, he was invited to go hunting near the concentration camp of Mauthausen. During the hunt he accidentally shot one of the beaters, a boy. One might have thought that as a high-ranking Gestapo man and SS officer he would have got away with a reprimand, but in these matters the Nazis were strict. He was sentenced to four months in prison. He was not required to serve out the sentence, but was instead sent to the front to lead a Sonderkommando, a taskforce whose function was to clean up behind the front and eliminate Jews, partisans and other so-called enemies of the regime. It was a death squad.

That hunting accident near Linz marked a dramatic rift in his life. Until this point, my father had been a so-called desk offender. Now he became an active perpetrator.

I

I started by requesting his SS files from the federal archives in Berlin. In the course of my research, I learned that my father met the men of his special command in July 1944 near Białystok in Poland. This was a deeply unpleasant surprise for me. I hadn’t known that he had done duty in Poland, a country to which I feel intimately bound. I studied Polish literature in Warsaw, and still consider Poland my second homeland. I first went to Poland just 20 years after my father had been sent there in an entirely different capacity.

In Białystok, the Sonderkommando 7a, also named Sonderkommando Bast after my father, took a group of old Poles as hostages and moved with them on to Warsaw. They set up camp outside the city in the summer of 1944, where the Warsaw Uprising was raging, as citizens fought to liberate the city from Nazi occupation.

When I started researching this, I came across documents that threw light on my father’s role. He was sent with his men into the city, heavily armed and in civilian clothes, to liquidate, as he put it himself, whoever they came across – unarmed civilians, insurgents or otherwise, men and women. He showed no mercy.

Was he blindly following orders? That’s only part of the truth. As commander of a taskforce, he was pretty much his own boss. So why did he do it?

Why do people turn so easily from being “ordinary men”, as the historian Christopher Browning describes them, into ruthless murderers, convinced that they are doing the right thing, and that they are serving a just cause? The historical record shows that when the state sanctions murder against minorities, people are more likely to perpetrate violence.

And when the conflict is over, they get on with their normal life as fathers and husbands. Society doesn’t seem to have much of a problem with reintegrating them. This is also true for the next generations. Most of my peers are still reluctant to face the reality of Nazi crimes, or to admit that many of their grandparents and parents had supported the Nazi regime as willing followers, or maybe even taken part in the crimes. They demand we draw a thick line under the past, and let bygones be bygones.

Anyone who insists on digging up the shameful past in which so many Austrians participated in the most gruesome crimes will not have a warm reception in my country. There are still large parts of society that think we should let the past rest.

In many cases, even the worst perpetrators slip back into their former professions as doctors and lawyers, engineers and craftsmen. Society needs them. After the total moral disaster of the second world war, we were sure that humanity had learned its lesson, that such crimes would never happen again, that the perpetrators would be outcast for a long time. Nie wieder (“never again”), was the universal slogan – but, as we know, it was short-lived.

M

My father was apparently the great love of her life. And he was 20 years younger than Hans Pollack. This might have been part of the attraction. My real father knew Pollack, but not very well. Pollack was also a Nazi, but they didn’t socialise as far as I know. When I was 18, I was asked by my mother if I wanted to change my name from Pollack to Bast – when I was born she was still married to Pollack, so his name is on all my papers. I thought about the change of names for some while, but then refused. Maybe this was motivated by the growing distance I was trying to put between myself and my father’s family in Amstetten, and the evil he embodied in my eyes.

And now another generation watches on helplessly as evil gains ground – in Europe and beyond.

I cannot and will not judge other people, but I know that I, as the son of a perpetrator, am not allowed to let this pass. Many people say that it is time to forget, to let the past rest – why dig up these gruesome things again and again?

But I believe we have a duty to remember. Yes, we can look ahead, but without forgetting the past. We must cherish the memory of the victims – and equally preserve the memory of the perpetrators and their crimes. Many victims seem to have disappeared without a trace – nameless, faceless, they have been burned to ashes in the ovens of extermination camps or thrown into pits somewhere to be forgotten for ever.

I wrote a book in 2014 called Kontaminierte Landschaften (“Contaminated Landscapes”), which dealt with this subject. These were the places where terrible things happened, mass murders whose victims had often been buried on the spot. I came across them regularly when researching the book about my father. In Poland and in Slovakia, where he served with his men, I found numerous “contaminated landscapes”, most of them anonymous, where his victims had been buried. Buried is not the right term: the murderers just threw some earth on them. In some cases they didn’t even bother to do that. Some were exhumed shortly after they were killed, but others have never been found – or rather, have never really been looked for. Let them lie in some hidden place. No stone, no Christian cross or Jewish matzeva to tell anybody who passes by to stop and consider that human beings have been buried here.

From Poland, my father was sent with his men to Slovakia to fight the uprising against the fascist regime there. Slovakia was then an ally of Hitler’s Germany. In Slovakia, I found many contaminated landscapes that my father’s men had left behind. They were sent there to hunt – literally hunt – Jews and partisans. My father was a passionate hunter and he was at home in the mountains. During my research, I came across an incident in the mountains near the town of Ružomberok in central Slovakia. In the small village of Bully, members of the Special Command 7a found a group of Jews hiding in the hut of a poor farmer’s wife. My father ordered them to be shot – along with the woman who had given them shelter. Some time later they were exhumed by local people and their remains, bodies and clothes, noted down precisely.

When the book was published in Czech, I received a letter from a woman in Prague who told me that a young couple with two children among the anonymous dead were her relatives, her uncle Jenö Kohn, a pharmacist in Banská Bystrica, with his wife and two children. And she sent a photograph of her uncle, a young, good-looking man. She wrote that she was glad that she had found out what had happened after such a long time.

That’s exactly what this process of bringing up the past is about. To try to give back to at least some nameless victims their faces and names, maybe even part of their history. The perpetrators had done everything to make them disappear for ever, to be erased from memory as if they had never existed.

I

In the beginning, the search for convinced Nazis to be put on trial seemed to be taken seriously, but soon the eagerness faded – more so in Austria than in Germany. The so-called denazification was not popular among most Austrians who had been followers of the regime or at least passive bystanders. Despite the fact that the great majority of Austria’s Jews had perished in the camps, antisemitism was still thriving. We can see it is rapidly gaining ground again today – perhaps my country’s greatest contemporary disgrace.

My father was on the run for two years, first in Austria, then in South Tirol, now part of Italy, where he found shelter and work with a rich farmer. Everybody knew that he was not a lumberjack as he pretended to be. The scars on his face from duels betrayed him. But nobody cared. South Tirol then was some kind of a no man’s land.

In March 1947, my father planned his return. My mother and I were to meet him in Innsbruck and accompany him on his onward flight to Paraguay, a safe haven for old Nazis like the notorious Josef Mengele. My mother only wanted to take me along. She planned to leave her other two children, my half-sister and my half-brother, behind with their father. My father already had the necessary papers from the Red Cross, which was then actively aiding Nazis to leave Europe for Latin America by issuing thousands of exit visas.

My father intended to cross the Italy-Austria border at the Brenner Pass. There he hired a young local man to guide him over the frontier, which was strictly guarded at night. His young South Tirolean guide was convinced that my father was carrying part of the legendary Nazi gold in his rucksack. He shot him, then hid my father’s body in a bunker. There was no gold in the rucksack, just some clothes and other worthless things. The body was found weeks later.

After my father’s death, my mother was in deep shock. I was too small to understand what was going on. We were then living in a village in the countryside as our house in Linz, Pollack’s house, had been bombed in late 1944. In those early years nobody told me anything – not about my real father, his plan to take my mother and me to Paraguay, or his death. Some time after my father’s death, my mother remarried Pollack – or rather, he remarried her. She had three children and no work. Pollack adored her. Without him, she would have been lost. In my family we didn’t talk much about the past – and I didn’t ask questions. I was not forbidden to ask, I just didn’t ask. That was it.

Last year, I received the Austrian police file about the murder on the Brenner Pass in March 1947. My father had been shot three times, twice in the face and once in the chest. Details I really didn’t want to know.

His life, a study in sustained violence and inhumanity, had been ended by a crime. Today we are confronted with the rise of violence and naked force again. Democratic Europe seems ill-prepared for this. People seem to prefer to close their eyes and ears once more. Let my family’s story be a warning.

This is an edited version of the Krzysztof Michalski Memorial Lecture, given at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna (iwm.at) in June 2024

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten

Opmerking: Alleen leden van deze blog kunnen een reactie posten.